Life is not a drill

Saturday, March 13, 2010 at 2:00PM

Saturday, March 13, 2010 at 2:00PM  Sometimes even bad days end up being great. So it was with a day I experienced a week ago. I had been asked to substitute for the teacher who I will replace in April (she will be on maternity leave April through June). The classes I will cover are retail store management, sales and marketing, and accounting.

Sometimes even bad days end up being great. So it was with a day I experienced a week ago. I had been asked to substitute for the teacher who I will replace in April (she will be on maternity leave April through June). The classes I will cover are retail store management, sales and marketing, and accounting.

The first thing to throw off my day was that I arrived to work and realized that I was missing my reading glasses. This is akin to suddenly becoming a derelict.

When I discovered that my glasses were missing, I considered going home to retrieve them, but quickly realized I wouldn’t have time to make the trip and get to class on time. So I drove to Walmart to buy some glasses. (Actually, I drove to Rite-Aid, which is closer, but it wasn’t open by 8:15 a.m., so I drove further to Walmart and sat in a line of traffic--both coming and going--waiting for road construction.)

Forty-five minutes later, I reported to the classroom with little time to spare. Students like to come into the classroom and hang out to eat before class and the teacher had told me that she’s happy to let them do it. About ten minutes before class was to start, I realized that I needed to use the restroom. I only had a few kids in the classroom and they were busy chatting and eating, so I figured I’d just hop across the hall to the restroom and be back before anyone noticed. Bad idea.

I was in the restroom about three minutes, but when I came out, I encountered mass pandemonium. Kids were rushing past me while one of the student store managers stood at the door to my classroom loudly commanding, “Hurry up! Everyone come in here!” It was obvious that something had happened during my absence, but I hadn’t heard an announcement, so I was bewildered as to what.

I asked the student manager, “What’s going on?” “A lock down,” she replied. Having worked at the high school for many years, I know that lock-down drills are planned in advance so that the teachers know about them, but the students don’t. This one was not planned.

The cafeteria emptied quickly and we shut the locked classroom door. The student manager had already placed a piece of paper over the door window (as required) and closed the window shades (also required). I was extremely relieved and impressed that these kids knew what to do and that they had done it.

I immediately walked to the back of the classroom where the emergency procedures were posted on the wall. Whoops, I couldn’t read them (thank goodness I purchased those new reading glasses). I returned to the front of the room, grabbed my glasses, and went back to read the instructions. I asked the two store managers to count all of the students in the room so that I could phone the main office with a count.

I phoned the office extension and left the message that I was in the classroom with 53 students..One of the students asked, “Is this a drill?” I replied, “I don’t know, but we should treat every drill as if it’s real.”

I tried calling the main office several times for information and finally got through to the head secretary. “Is this a drill?” I asked. “No, it is NOT,” she said emphatically. I hung up the phone and announced to the students that it was not a drill. I asked them to turn off their cell phones and to move away from the windows.

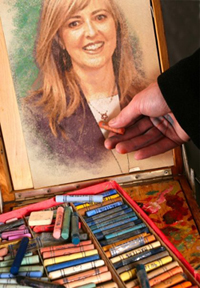

The kids were very cooperative and lowered their conversations to whispers. I sat on the edge of the desk in the front of the room waiting along with the students for the next announcement. It occurred to me that the classroom we were in was one of the worst possible locations should an intruder want to break in (see photo, above). The classroom sits on the edge of the campus courtyard with two large windows at each corner.

During the few minutes that we waited for another announcement, there were a lot of things going through my mind. I wondered what I would do if someone tried to enter the locked room. I wondered if we could make a break out the emergency side door. I wondered if this was some kind of test.

I wasn’t frightened, but on heightened alert. This has not happened but once during the nine years I have worked at the high school. Finally, after several minutes, the principal announced over the intercom that we could move freely within the building, but advised everyone to stay away from the perimeters of the campus. I later found out that shots had been fired near the hospital, which is close to the high school campus. The police department had asked for a lock-down as a precautionary measure until they could locate the perpetrators.

In retrospect, it occurred to me that going through the entire experience was good for me. I’ll be better prepared should there ever be a “next time.” It also occurred to me that most of us treat life as if it’s a drill. When something “major” happens, we go on heightened alert and become quite sober. Once the crisis passes, it’s back to our usual slothful ways. I feel immensely grateful that I was given a wake-up call as to what’s important in my life before I reached my deathbed. But, you know? I still treat life as if it’s a drill most of the time.

Becoming Orthodox has greatly helped me to understand that my life is not a drill. Orthodoxy is kind of like the Marine Corps. of Christianity. So many things we are encouraged to do are a real head-butting of our culture (thank you to Father David for that word picture). I find that as I use the tools I’ve been given as an Orthodox Christian, I am slowly being changed inside.

Becoming Orthodox has greatly helped me to understand that my life is not a drill. Orthodoxy is kind of like the Marine Corps. of Christianity. So many things we are encouraged to do are a real head-butting of our culture (thank you to Father David for that word picture). I find that as I use the tools I’ve been given as an Orthodox Christian, I am slowly being changed inside.

One of the best tools I’ve been given is this thing called “confession.” Oh, sure, as a Protestant Christian, I would occasionally feel guilty about my personal failings and offenses. I would even pray about it sometimes. You know, the typical “pillow talk” that we do when no one is around but us and God.

But there was this thing missing: accountability. Well, yes, I sometimes attended a small group study or had lunch with a Christian friend where I unloaded my feelings. I wasn’t altogether a lost cause. When the guilt, depression, and anxiety got to be too much, there was always a counselor—someone I could pay to hear me out, offer suggestions for improvement, etc. But looking back, it seems it was mostly an exercise to relieve me of my psychic pain (which wasn't all bad).

Along came Orthodoxy and I began to learn the practices of the ancient Christian faith. I learned that the early Christians actually confessed to one another publicly. You can imagine how difficult that would be! You stood up in the midst of the church community and confessed your sin, thereby healing your relationship with others. When problems with that system arose, the priest began to stand in the place of the community. So we also confess our sins to the priest because he is a man, created and fallible just like everyone else--standing in the place of everyone else.

All that I ever knew about confession before becoming Orthodox was what I’d seen in movies and it always involved Roman Catholic confession. You know the typical scenario: some poor (probably ADHD) kid is forced by a religiously zealous parent or other authority figure to sit in a dark, cramped confessional booth and mutter some embarrassing story about how he hasn’t confessed for six months and how he sometimes has lustful thoughts about girls. The priest is usually some version of Bing Crosby’s good natured Father O’Malley or—more likely in current movies—a closet pervert (I’m picturing Christopher Walken in the role), who gets off on hearing the juicy details of his parishoners’ confessions. Seen it a million times.

All that I ever knew about confession before becoming Orthodox was what I’d seen in movies and it always involved Roman Catholic confession. You know the typical scenario: some poor (probably ADHD) kid is forced by a religiously zealous parent or other authority figure to sit in a dark, cramped confessional booth and mutter some embarrassing story about how he hasn’t confessed for six months and how he sometimes has lustful thoughts about girls. The priest is usually some version of Bing Crosby’s good natured Father O’Malley or—more likely in current movies—a closet pervert (I’m picturing Christopher Walken in the role), who gets off on hearing the juicy details of his parishoners’ confessions. Seen it a million times.

So it was with some fear and ignorance that I approached confession. And here’s what I’ve learned: there’s no dark confessional booth, the priest isn’t a buffoon or a pervert, and confession is not about judgment--it’s not even about guilt or some legal concept of getting God off your back. But going to regular confession teaches me to be sober—about my life and how I’m living it.

Here’s a good explanation of what I’m talking about, from a writing by Phil Thompson (who goes by the saint name, “Silouan”):

Soberness. The church fathers write about "nipsis" which is watchfulness, awakeness, as when Christ asked the disciples at midnight "Couldn't you watch one hour?" We tend to sleepwalk from one stimulus to another, and as adults we've got programmed responses that can carry us through a whole day without ever really engaging with eternal things. Like the way I can get from home to work in the morning without ever consciously steering or even remembering the drive. Watchfulness is the opposite of that: intentionally keeping guard over our thoughts and what comes in through our senses, and cutting off reflexive ways of thinking or acting. When I'm in the habit of taking a fearless and searching moral inventory and sharing that with another person regularly, it starts to build a habit of watchfulness over the state of my heart, a habit that lasts beyond the little while I spend preparing for confession.

Confession helps me to treat my life like it’s the real deal—not a drill. I’m forced to take a penetrating moral and spiritual inventory—on a regular basis.

But what about the priest? Why involve him? Well, as I mentioned before, the priest stands in the place of the community. Confession is also a gift from God that allows us to not only confess our sins, but to receive the assurance of God's forgiveness and the spiritual guidance that we need to help us overcome these sins (sin, literally translated, means "missing the mark").

From this website: In the Orthodox Church, the priest is seen as a witness of repentance, not a recipient of secrets, a detective of specific misdeeds. The "eye," the "ear" of the priest is dissolved in the sacramental mystery. He is not a dispenser, a power-wielding, vindicating agent, an "authority." Forgiveness, absolution is the culmination of repentance, in response to sincerely felt compunction. It is not "administered" by the priest, or anybody else. It is a freely given grace of Christ and the Holy Spirit within the Church as the Body of Christ.

I’ll let Silouan’s words further elaborate:

As a Protestant I was familiar with "accountability groups" or partners--something like the ancient Irish practice of having an "anamchara" or soul-friend. Unfortunately, in my experience, these arrangements don't work in the long term without getting strange.

Most men aren't well-suited to being that intimate with another man who's his peer. And it's hard not to fall into either judgment or commiseration ("Oh, me too! I hate that!"). The way confession has developed in most of Christianity is as part of a pastoral relationship.

I confess with my priest, but he doesn't confess with me--he's got his own spiritual father. And my priest, though he's a friend, isn't a buddy--he's in a role more like a father or sensei, and I come to him for correction and counsel in a way I don't with others. Also, he's familiar with a huge volume of canons and information about the way sins and passions work, and what helps a person struggle against them. That equips him to give effective counsel in a way most others can't.

I'm learning that confession is where I go to find the love of Jesus Christ in tangible form. I feel like my attempt to expound on the topic falls woefully short. I'll let one of my favorite writers, Anthony Bloom, have the last word. Here's a passage from one of his writings about confession.

Reader Comments (1)

That was very interesting about confession. Enjoyed.